Whilst in Germany a friend of ours told us that La Palma was experiencing many earthquakes. I checked and she was right.

The earthquakes were very frequent, every few minutes, and constituted what is known as an earthquake “swarm”. This is a good indication that magma (lava) was moving under the island and a volcanic eruption was possible, even likely.

I have an interest in volcanoes and earthquakes so I followed this avidly. Sure enough at 1410 local time in the afternoon of the 19th September a volcano erupted.

The location of the eruption was just 8km away from the marina where the boat was located. Neither Angelika nor I were comfortable with the fact that “Maya” could very quickly be in danger or even damaged. We made the decision that I should fly out there and monitor the situation.

Two days later I was on a plane bound for La Palma. There were just 35 people on the aircraft; The crew said that many travel companies had cancelled holidays that weekend because of the eruption. They also told me that the return flight was completely full.

I arrived at the marina without problems after initially worrying that the taxis couldn’t get past the volcano. The taxi ride there took me right past the volcano (no more than 2km from the road). In the daylight it wasn’t so impressive as all you could see was the ash shooting up into the air and an orange glow at the bottom.

From the marina it was very different. You could feel and hear the sound of the volcano roaring. You could see the (luckily) light ash fall from the previous day.

As the early evening came the volcano became more and more visible.

I went out for a pizza dinner with our Dutch friends and chatted about the volcano. The whole evening was punctuated with window shaking explosions and the ever present angry roar from the volcano.

Every evening and morning I took the opportunity to take pictures (and learn how to use the camera in low light situations!) These were generally the best times to take pictures as the sky is darker.

During the night you could hear the volcano roaring and feel multiple subsonic explosions. A sound I will never forget.

I will also never forget the volcanic ash and dust that rained down onto the boat during the day. Not always but enough that I had sweep/wash the boat often. Then the next morning, or even later in the same day, it would be back again.

The problem is that the ash is very fine and gets into everything. I had to wash the deck fittings and blocks as they would not move or turn. Every mooring line was covered in it, every sheet and halyard black with dust.

I had to wear glasses and even carry an umbrella to escape the worst of it – I think I’ll be finding the black ash and dust for a long time after this is all over.

My problems were nothing compared to the local people who had to evacuate their homes within an hour as lava flowed from the volcano. All of a sudden it became both incredibly beautiful and also incredibly dangerous and destructive.

The local news carried pictures of people loading what they could onto the back of lorries or vans and leaving their homes forever. Nothing would be left if they ever returned – a very sobering thought.

For a few days it was an incredible spectacle and people would come into the marina just to watch it and experience what could be a once in a lifetime event. There were reporters and TV crews everywhere. I was even interviewed and my picture and story appeared in a Canaries online newspaper (www.eldiario.es)

Here’s the link to the story in Spanish – Deepl translator (or Google Translate if you must) will help.

Then reality struck. The lava was going to enter the sea at a place called “Las Girres” where we had previously enjoyed sunset dinners and drinks. This was but a few miles from the marina. The big worry was that upon reaching the sea, the lava would release toxic and corrosive gases.

On the night of 29th September at around 2300 the lava reached the sea. All of a sudden the marina was full of blue flashing lights, “Guardia Civil” and local police all running around and shouting that we all had to leave the marina (not with the boat). I wasn’t sure what to do but the Policeman on my pontoon was very insistent that I go. I grabbed some money, my mobile phone and the boat keys. I locked the boat and got off; all the time the policeman was yelling “Vamoos! Vamoos!” so I “vamoosed” out of the marina with many other people, some wearing gas masks, and many of them in cars.

When I got to the gate I didn’t know where to “vamoos” to, so I walked towards the port and sat on a bench wondering what to do next. Looking back at the marina I could see some of the lights occasionally being obscured by a shimmering haze. I thought this must be the gas they were worried about.

I started thinking about possible damage to the boat and if I would be able to return – I started to understand something of how the poor locals, loading their lives into the back of van at a moments notice, must have felt.

At around 0300 I noticed that the marina lights no longer had a “haze” around them and walked back to the marina. I arrived only to find the gates locked and Guardia Civil and Police there preventing entry.

I asked a tall and luckily friendly Guardia Civil officer if I could go back in. Understandably he wanted to know why, so I explained what had happened and the fact I had nowhere else to go and nothing with me. He considered this for a minute and then called his boss and the “PEVOLCA” people (who were co-ordinating the reponse to the situation). After a few minutes discussion he told me I could return to the boat as long as I sealed all the windows and doors. If the situation became worse they would come and find me again.

There then followed a restless night whilst I considered what to do. It was clearly time to move on to another marina, or even another island.

The following morning everything seemed back to normal in the marina other than it was very quiet.

I went into the office and talked to the marina staff there. Apparently the previous night (when I was forcefully evicted) was a mistake; the police were only supposed to clear the marina of spectators and film crews. Clearly no-one told the guy clearing my pontoon. The scary haze I had seen around the marina lights was nothing more than sea-spray.

One of the reasons I had stuck around so long was to receive two large packages (Angelika’s SUP and some solar panels). We’d been trying to get the SUP to the boat for three years! There, sitting on the floor of the office were the two large packages. They’d arrived that morning in spite of the volcano.

The marina guys moved the parcels onto the boat for me and then there was really no reason for me to stay. Our Dutch friends had already left the marina a few days before, as had many others. Some other friends were due that day and I had promised to meet them for pizza in the evening.

I spent the rest of that day cleaning the ash and dust off the boat and generally tidying up to get the boat ready for the trip – I had decided the island of El Hierro was the safest and easiest option.

That evening, over pizza and wine, I discussed what to do with the recently arrived friends. They decided that they too would leave the island as soon as they could. Their boat was on the land and was due to be launched the next day.

Two days later I cleaned the boat for a final time and said my “goodbyes” to the marina staff.

The weather forecast was for an expected F4/F5 out of the north-east – a good direction for the trip to El Hierro.

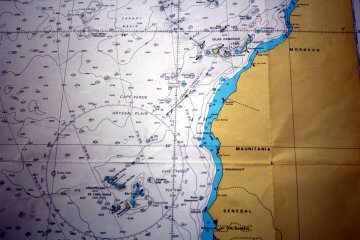

First I had to sail directly west away from the island to get outside the 2 mile exclusion zone. This zone is heavily patrolled by a big Coast Guard ship (the “Punta Salina”) and several smaller vessels. They noticed me coming out and the “Punta Salina” lazily turned to head towards me. I checked my course and I knew it was OK. The “Punta Salina” passed slowly by at about 500m away and carried on. I must have been doing the right thing!

As I turned south and prepared to put the sails up, the volcano gave me one more light shower of volcanic ash as a parting gift. Unfortunately all I could see of it was a grey/black haze.

Away from Fuencaliente (south of La Palma) the wind gradually built until I had a steady 24 knots (F6), gusting 30 knots (F7). This was “apparent” wind which is the wind the boat feels. As I was heading downwind the real wind was in the order of 30 – 38 knots (F7 – F8).

The boat was racing along at (I believe) the fastest we’ve ever gone. Our maximum speed was 9.5 knots, and we averaged around 7.5 – 8 knots.

The stronger than expected wind meant that the waves were considerably larger than I was anticipating. Instead of 1.5m to 2m I would say they were 2.5m – 3.0m, sometimes larger.

The boat took it all in her stride although occasionally a particularly boistrous wave would either shower us with a wall of water, push the boat further over than I would have liked, or more usually both!

I still managed to make beans on toast (using up the last of my homemade bread) and have tea & biscuits. At no time did I feel worried.

As we approached El Hierro the wind dropped a little and I cautiously put out more sail. It didn’t last and soon came back even stronger. At this point we were only about 6 miles away so I opted to put the sails away and motor the last few miles.

I had decided to put the fenders and ropes on in the shelter of the outer harbour, but in the event the boat was steady enough for me to do it before I got that far.

As I rounded the harbour wall there was a gust of 45 – 50 knots (F9 – F10) which surprised me a little, but it lasted just 30 seconds or so. However the sea did manage to send one rogue wave over the front of the boat and over me!!

Our Dutch friends had promised to help me get in and sure enough they were waiting at the berth along with most of the other “residents” of the marina, about 20 people in all. There were abundant helpers and applause – what an entrance!!

After I had said thanks to all, tidied the boat (much stuff had fallen off the shelves – the less said about that the better), had a shower etc., I was invited to the Dutch boat for a very welcome G&T or four!!

I slept well that night, happy to be safe from the volcano.

As I write this the volcano remains extremely active. The locals cannot, however, simply get on their boat and sail away.